Lecture 7 - Transactions and concurrency pt.2

# Locks and Time

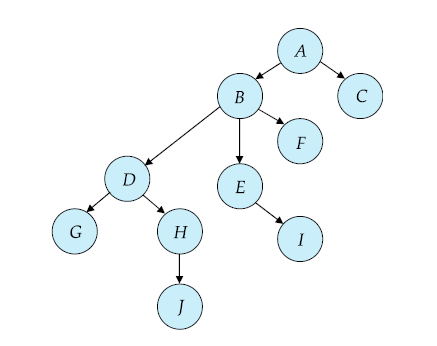

# Tree Protocol

- Only exclusive locks are considered.

- The first lock may be on any data item.

- Subsequently, a data item can be locked only if its parent is currently locked by the same transaction.

- Data items may be unlocked at any time.

- A data item that has been locked and unlocked cannot be subsequently re locked by the same transaction.

The tree protocol ensures conflict serializability as well as freedom from deadlock

Drawbacks

- Protocol does not guarantee recoverable or cascadeless schedules

- Need to introduce commit dependencies to ensure recoverability

- Transactions may have to lock data items that they do not access increased locking overhead, and additional waiting time potential decrease in concurrency

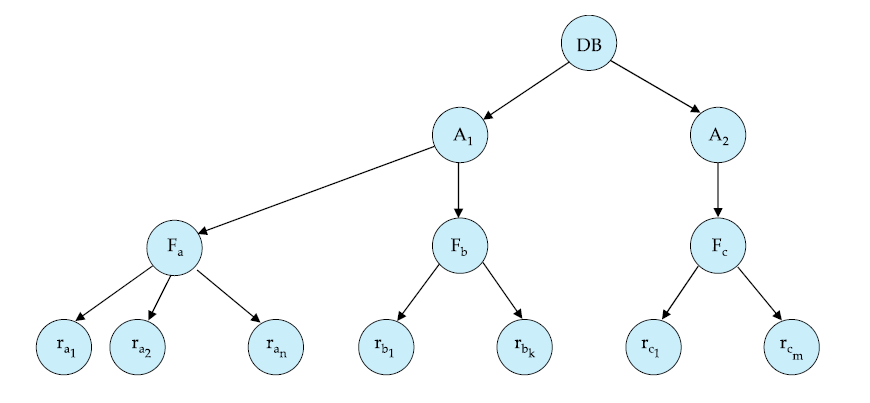

# Granularity Hierarchy

The levels, starting from the coarsest (top) level can be

The levels, starting from the coarsest (top) level can be

- database, area, file, record

- database, table, page, row (as in SQL Server) etc.

When a transaction locks a node in S or X mode, it implicitly locks all descendants in the same mode (S or X).

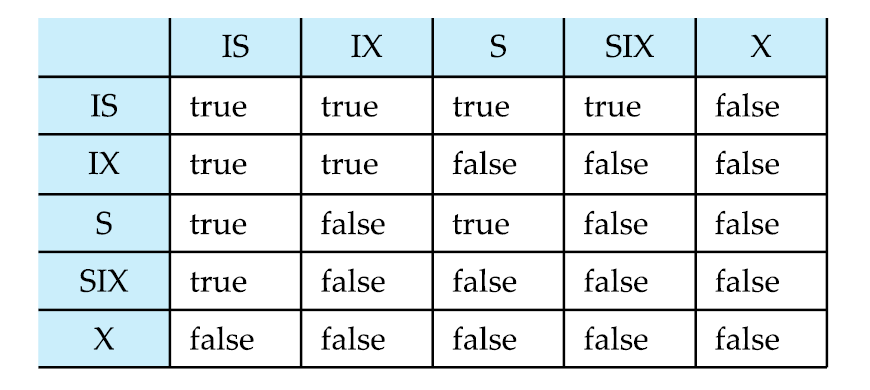

# Intention Lock Modes

- intention shared (IS): indicates there are shared locks at lower levels of the tree

- intention exclusive (IX): indicates there are exclusive or shared locks at lowers level of the tree

- shared and intention exclusive (SIX): a shared lock, with the possibility of having exclusive or shared locks at lower levels of the tree.

- The root of the tree is locked first in some mode (IS, IX, S, SIX, X).

- If a node is locked in IS mode, its descendants can be locked in IS or S mode.

- If a node is locked in IX mode, its descendants can be locked in any mode.

- If a node is locked in S mode, its descendants are implicitly locked in S mode.

- If a node is locked in SIX mode, its descendants are implicitly locked in S mode, but can also be locked IX, SIX, or X mode.

- If a node is locked in X mode, its descendants are implicitly locked in X mode.

# Timestamp Based Protocols

Each transaction Ti is issued a timestamp TS( Ti ) when it enters the system.

- Each transaction has a unique timestamp

- Newer transactions have timestamps greater than earlier ones

- Timestamp can be based on wall clock time or logical counter Timestamp based protocols manage concurrent execution such that timestamp order = serializability order

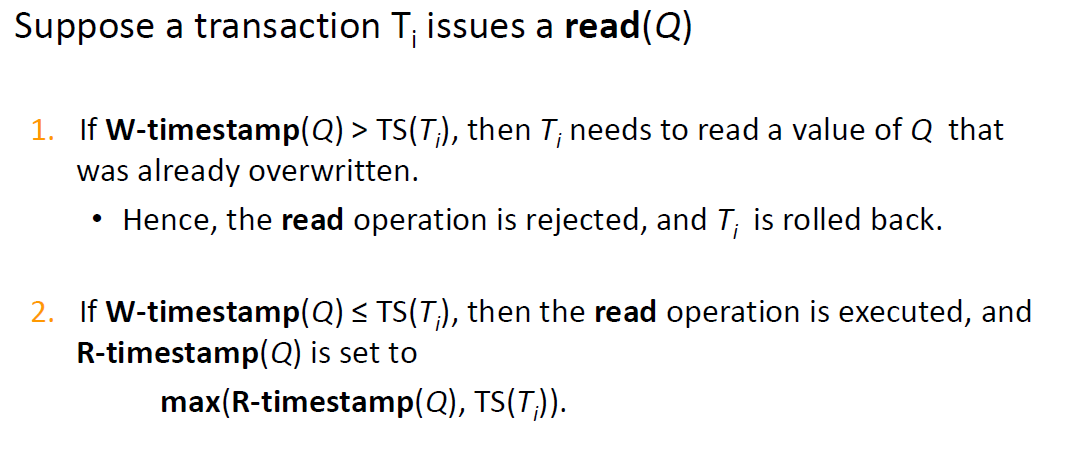

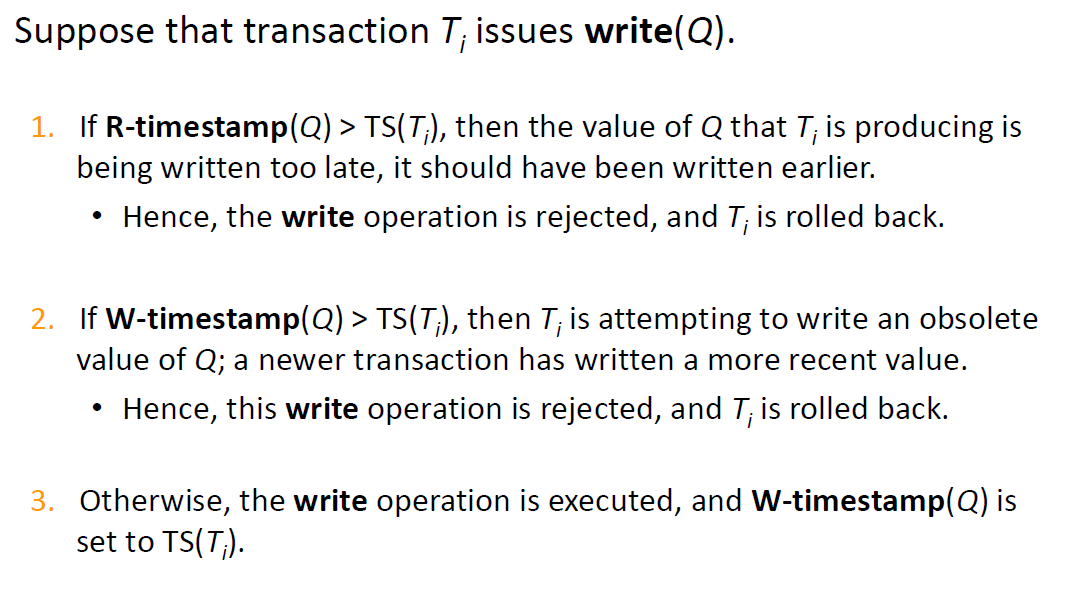

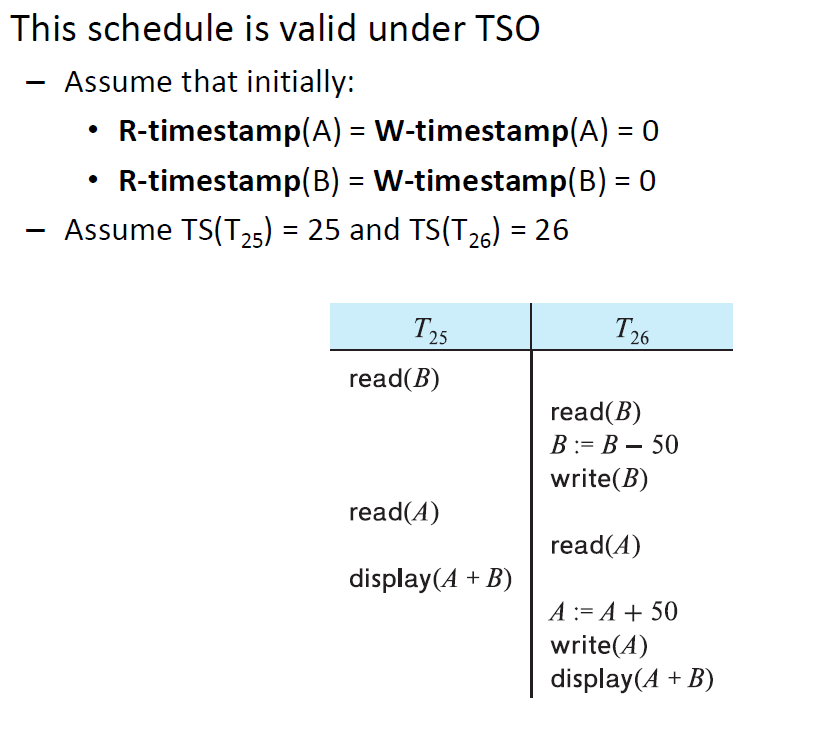

# Timestamp Ordering Protocol

Maintains for each data Q two timestamp values:

- W-timestamp( Q ) is the largest timestamp of any transaction that executed write( Q )

- R-timestamp( Q ) is the largest timestamp of any transaction that executed read ( Q )

Imposes rules on read and write operations to ensure that

- Any conflicting operations are executed in timestamp order

- Out of order operations cause transaction rollback

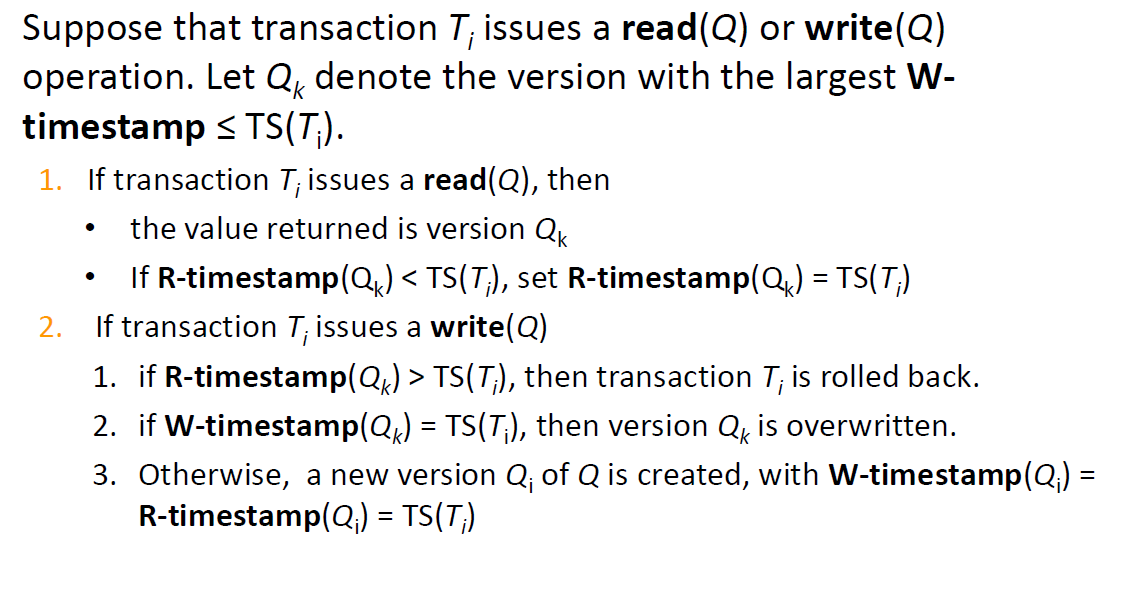

# Multiversion Timestamp Ordering

- Each data item Q has a sequence of versions < Q 1 , Q 2 ,…., Q m >

- Each version Q k has its own timestamps:

- W-timestamp( Qk ) timestamp of the transaction that created (wrote) version Qk

- R-timestamp( Q( k ) largest timestamp of a transaction that successfully read version Qk

Notes

- Read requests never fail and never wait.

- A write by Ti is rejected if some newer transaction Tj that should read Ti ’s version, has read a version created by a transaction older than Ti

- Protocol guarantees serializability

- but does not ensure recoverability or cascadelessness

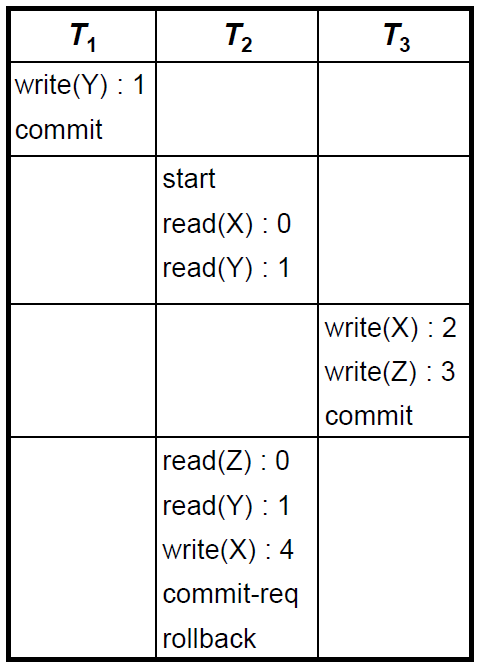

# Snapshot Isolation

- Widely used in practice (incl. Oracle, PostgreSQL, SQL Server, etc.)

- Each transaction is given its own snapshot of the database

- Transactions that update the database have potential conflicts

- Read requests never wait

- Read only transactions never fail

Snapshot isolation does NOT ensure serializability

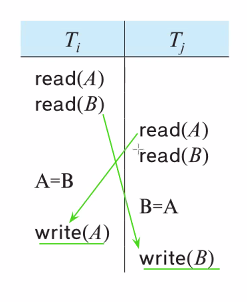

- Ti reads A and B , updates A based on B

- Tj reads A and B , updates B based on A

- Updates are on different objects; both are allowed to commit but the result is not equivalent to a serial schedule

- Schedule is not conflict serializable Precedence graph has a cycle

- This anomaly is called a write skew

Lecture 6 Transactions and concurrency | Lecture 8 Database Recovery